Cultural History of cosmetics

Looking back over Japanese history, we know from passages in the chronicles Kojiki and Nihon shoki and from traces of color on the clay haniwa figurines made during the Kofun period (300-710) that in ancient times there was a custom of painting the face with red pigments.

This primitive use of cosmetics evolved into a more aesthetic approach in the latter half of the sixth century, when rouge, powder, and other forms of makeup were imported into Japan along with other aspects of culture from the China and Korean peninsula. In 692, a Buddhist priest Kanjo is said to have been the first to make lead-based face powder in Japan, and delighted Empress Jito by presenting this new invention to her.

During the Heian period (794-1185), especially after the suspension of Japan’s embassies to Tang China, cosmetics in Japan shifted from an imitation of Chinese models to a style more attuned to the Japanese sensibility: women wore their hair very long and straight, almost reaching the floor; applied white face powder, plucked their eyebrows and repainted them higher on the forehead; and blackened their teeth.

With the advent of the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the culture and institutions of the warrior houses were perfected, and cosmetics are mentioned in a number of writings from this era. Illustrated texts such as Shichiju-ichi-ban shokunin uta-awase (Poetry Contest Among People of Various Occupations in Seventy-One Rounds) show us that by this time craftsmen of rouge and face powder were well known to urban people.

Looking back over Japanese history, we know from passages in the chronicles Kojiki and Nihon shoki and from traces of color on the clay haniwa figurines made during the Kofun period (300-710) that in ancient times there was a custom of painting the face with red pigments.

This primitive use of cosmetics evolved into a more aesthetic approach in the latter half of the sixth century, when rouge, powder, and other forms of makeup were imported into Japan along with other aspects of culture from the China and Korean peninsula. In 692, a Buddhist priest Kanjo is said to have been the first to make lead-based face powder in Japan, and delighted Empress Jito by presenting this new invention to her.

During the Heian period (794-1185), especially after the suspension of Japan’s embassies to Tang China, cosmetics in Japan shifted from an imitation of Chinese models to a style more attuned to the Japanese sensibility: women wore their hair very long and straight, almost reaching the floor; applied white face powder, plucked their eyebrows and repainted them higher on the forehead; and blackened their teeth.

With the advent of the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the culture and institutions of the warrior houses were perfected, and cosmetics are mentioned in a number of writings from this era. Illustrated texts such as Shichiju-ichi-ban shokunin uta-awase (Poetry Contest Among People of Various Occupations in Seventy-One Rounds) show us that by this time craftsmen of rouge and face powder were well known to urban people.

By the early Edo period (1600-1868) there were elaborate treatises on etiquette and deportment for women that also gave detailed instructions on the proper use of cosmetics. During this period cosmetics centered on a palette of three basic colors: red (lip rouge, fingernail polish), white (face powder), and black (tooth-blackener, eyebrow pencil).

During the Edo period women were especially concerned with the application of face powder, for a white skin was regarded as the essence of a beautiful woman, as an old saying had it, "a light skin conceals seven other defects."

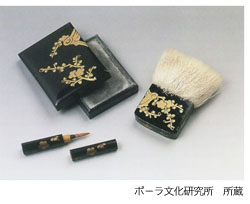

Face powder was a white, lead-based pigment dissolved in water and applied with the hands or a broad, flat brush. In the late Edo period, one brand of face powder called Bien Senjoko attained lasting fame by doing advertising tie-ins with a publisher of ukiyo-e prints.

Pigment for rouge was made primarily from safflowers, and applied to the lips, cheeks, and fingernails. Like face powder, a light application was regarded as a mark of refinement. In the late Edo period, however, there was a fad for heavier application of lipstick for an iridescent effect. Pigment from fresh safflowers became so expensive it was said to be worth its weight in gold.

The practice of blackening the teeth, a female rite of passage deeply associated with coming-of-age and marriage since the Middle Ages, became firmly established from the middle of the Edo period onward as a symbol of a woman’s married status: women would blacken the teeth immediately before or just following their wedding, and would shave off their eyebrows upon the birth of their first child.

Women of a certain age who belonged to the nobility or upper ranks of samurai society would use makeup to paint a second, artificial set of eyebrows higher on their forehead after having shaved off their natural ones.

As Japan entered modern times, an official government decree of the third year of the Meiji period (1870) outlawed the practice of tooth-blackening and eyebrow shaving among the peerage; and after Empress Meiji herself gave up blackening her teeth in 1873, ordinary women gradually followed suit. Around 1877, concerns over lead poisoning inspired a quest to develop a lead-free face powder, which was finally brought to market in 1904.

In the Taish period (1912-26), with the advancement of women in society and the workplace, quick and convenient makeup and cosmetics as an aid to social interaction began to be proposed. Face powder began to be sold in a broader range of tints other than the traditional white, and tube lipstick using other pigments and dyes began to replace the traditional safflower-based rouge. Vanishing creams, cold creams, and emulsions also appeared on the market, as cosmetics became increasingly westernized from the 1910s onward.

After World War II, beginning in the 1950s, Japan was heavily influenced by the American mass media, especially magazines and movies. In 1954, pancake makeup was introduced to Japan from the US, and from that time onward makeup cosmetics became a focus of general interest. In the 1960s, the trend in cosmetics shifted to an emphasis on makeup for the eyes and mouth, and starting about 1975, fads such as the surfer look and heavily made-up eyebrows swept women in their teens and twenties in particular.

Present trends include an individual approach to makeup, nail art and other fingernail decoration, and medicated cosmetics. The white-skinned beauty of the Edo period is no longer the ideal; we are now in an age in which consumers expect cosmetic products to serve a variety of needs and skincare functions.